Soap

Opera Weekly,

2000

|

|

Home | Cette page en Franšais |

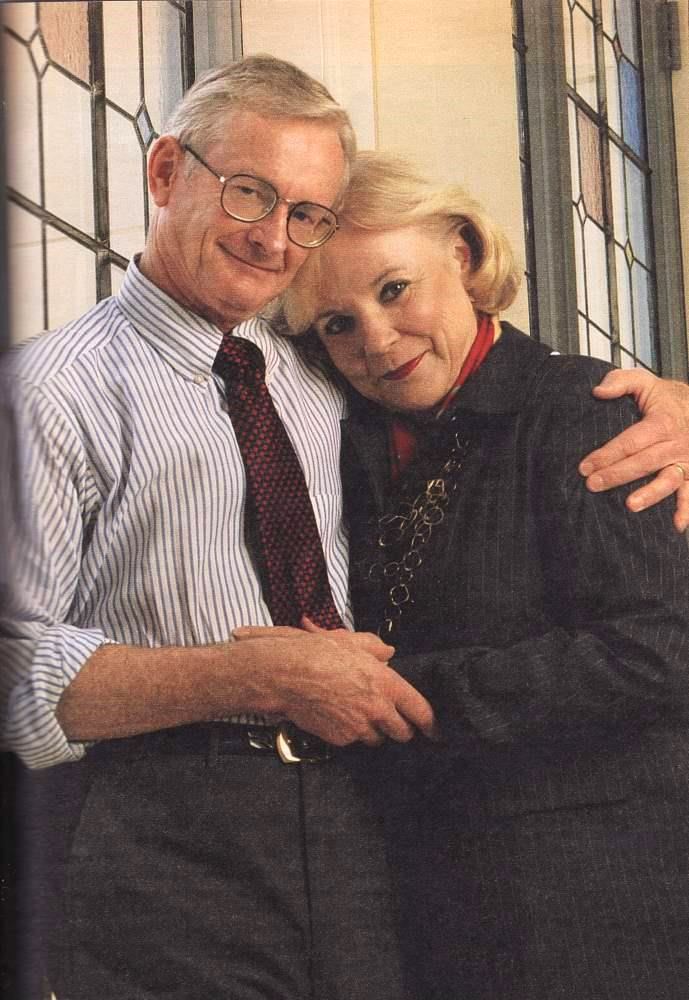

| Soap

opera's 25 most intriguing people : Jerome and Bridget Dobson, creators /

head writers |

|||||

|

Soap

Opera Weekly,

2000 |

|

||||

While

Bridget and Jerome Dobson don't exactly confirm the widely held theory that

their life together was played out on screen via the wild and wacky Augusta and

Lionel Lockridge, they don't exactly deny it, either. In truth, their own

anomalous backstories and the saga of their fictional love child, Santa Barbara, register

high on the suds-o-meter. She was born into the genre, the daughter of General

Hospital creators Doris and Frank Hursley, but the Dobsons earned their

reputation as master storytellers during an Emmy-nominated head writing gig at Guiding

Light (they created the Spauldings) and later As the World Turns. In

1987, they took center stage in a dramatic plot of their own when they were

locked out of the Santa Barbara studio after trying to fire co-head writer Anne

Howard Bailey; they sued NBC and New World Productions over creative control of

the show. Today, the Dobsons live in Atlanta, where they built their dream

house, write (she's done a musical; he's working on a novel), paint (Bridget's

had a one-woman show of her oils) and "we have friends now. We never had time to

have friends."

While

Bridget and Jerome Dobson don't exactly confirm the widely held theory that

their life together was played out on screen via the wild and wacky Augusta and

Lionel Lockridge, they don't exactly deny it, either. In truth, their own

anomalous backstories and the saga of their fictional love child, Santa Barbara, register

high on the suds-o-meter. She was born into the genre, the daughter of General

Hospital creators Doris and Frank Hursley, but the Dobsons earned their

reputation as master storytellers during an Emmy-nominated head writing gig at Guiding

Light (they created the Spauldings) and later As the World Turns. In

1987, they took center stage in a dramatic plot of their own when they were

locked out of the Santa Barbara studio after trying to fire co-head writer Anne

Howard Bailey; they sued NBC and New World Productions over creative control of

the show. Today, the Dobsons live in Atlanta, where they built their dream

house, write (she's done a musical; he's working on a novel), paint (Bridget's

had a one-woman show of her oils) and "we have friends now. We never had time to

have friends."

How did you start your career path ?

BD : By begging my way into writing General Hospital. My parents thought I was a "party girl" and really did not want me to write with them or for them. Finally, in one catastrophe night, I said, "I'm leaving the family unless you let me write," and they agreed to let me write one scene.

How old were you at that time ?

BD : 21

JD : And before too many months had passed, Bridgie was writing all five scripts.

Jerry, how did you become a soap writer ?

JD : I was busy learning Far Eastern history and farming while Bridgie was writing, but every so often I would look over her shoulder and she would let me write a line or two.

BD : When Procter and Gamble hired me at Guiding Light, which was going to an hour a day, I had never written an hour a day, and I couldn't tell Procter and Gamble that I was scared. So I said to Jerry, "This job may be too big for me," and he said, "Well, let me help you."

How did you meet ?

BD : We met at Stanford, my freshman year; I was in the book line and Jerry was in front of me...

JD : ...but in the next line over. And I took a look at this cute chick and fell in love instantly. I gallantly asked if I could carry her books back to the dorm. She said yes; she had 10 times the books I did, and staggering back with perspiration flowing down my brow, I asked for a date, and she said no. I said, "How about the following week ?" She said no; "how about the week after that ?" She said no. Boy, oh boy, it was clever strategy on her part. Perseverance eventually won out. This girl just took over my life.

Jerry has referred to you as the boss, Bridget. Were you ?

BD : I taught him everything he knew, and then he learned more than I knew, and he became boss.

JD : We sort of became more equal as time went on.

BD : He was a little more equal than I was, but anyway...

Did your personal and professional lives become one ?

BD : Sometimes they became one; in many ways we have been - and are - in sync on emotional and aesthetic issues. We came close to the brink of divorce, because we were really at each other's throats on occasion.

JD : Mainly over business things.

BD : More during the lawsuit period.

Did you ever tap each other on the shoulder in the middle of the night and say : Oh, I think Augusta should do this ?

JD : Some of our best thinking was done while we were asleep.

What

was your biggest success and your biggest failure ?

BD : Santa Barbara launching an hour. Nobody had done that before, in a new studio where we didn't even know how to turn on the lights. It led the way in terms of humor and understanding dysfunctionality and touching on intellectual concepts, and I think it was riveting for a while.

Do you consider the lawsuit a success ?

BD : It was a huge thing. We won major settlements in both (one against New World and one against NBC), but clearly, contractually, we had a lock on the win, and there was never any doubt. In terms of the show, it was devastated; in terms of our bank account, it was flushed.

So, do you consider that a failure ?

BD : In terms of the show, It was a failure. If our contracts were breached again we would do it, but we wouldn't want to.

JD : We regret the whole fracas; it should never have happened.

What motivates the two of you ?

BD : We're loaded with unending creative energy.

If you had your life to do over again, what would you do differently ?

BD : I'd be born to rich parents and never do soap opera. (Laughs)

JD : I would have probably spent my life eating Three Musketeers and ice cream sandwiches.

Was there one fork in the road that changed your life or lives ?

JD : Saying that we didn't want to write soap opera anymore and retiring from As the World Turns. That's when NBC came to us and said, "What would it take to get you back into the business ?" That's basically when they had to give us Santa Barbara.

Was there one moment where the success was as rewarding as anything you could have imagined ?

JD : There was a period of some months where we all felt that the stories were strong, were intertwined, that it all flowed so beautifully. Everything was in a kind of zone, and it was really hot and cooking. One of the high moments was during the lawsuit when several people giving depositions were very supportive of us, and at considerable peril to their own careers.

BD : That was very deeply touching. Because they acknowledged under oath that they knew they were risking their jobs.

Who was your individual or joint mentor ?

BD : We got a lot of good, basic advice on drama and story from Bob Short and Ed Trach at Procter and Gamble. Besides my parents, they taught us as much as we learned from anyone.

What's been the biggest obstacle or stumbling block that you've overcome professionally ?

BD : It was impossible for Anne Howard Bailey to get inside my head, and I could not get in her head. She has a darker view of life than I do; I think she thinks of me as Pollyanna, and I think of her as Darth Vader.

JD : We found generally the network was set in cement and had trouble seeing the whole forest for the trees.

When

starting Santa Barbara, if you knew

then what you know now, would you have stuck more with the writing and

not so much with the business end ? Did

it take anything away from the creative experience ?

When

starting Santa Barbara, if you knew

then what you know now, would you have stuck more with the writing and

not so much with the business end ? Did

it take anything away from the creative experience ?

BD : Absolutely nothing.

JD : Yes, but there was something absolutely wonderful about putting the show together so that you were in control of all aspects from hairstyles, to sets, to the basic look of the show. The creative process that we focused on the written page expanded to the studio and to the actors, and that was a step beyond where we had been.

You indicated that your marriage went through some rough times because of the lawsuit. Was it too big a price to pay for creative control of the show ?

BD : I think it was worth it in some ways. What I would have done differently is hire a couple of hot-shot businessmen/accountants who could handle the legal and business end, but we would not be involved with it.

What do you think people would be surprised to know about the two of you ?

BD : How we laugh in the middle of the day, in the middle of the night, in any given situation, somehow.

JD : We find fun.

What is a common misconception about you ?

JD : That I'm incredibly handsome. That we're ornery, mean, nasty people.

Whom do you find intriguing ?

JD : One of the most interesting people we met was Freddie Bartholomew, who produced As the World Turns. He had a million wonderful stories to tell, and he was an absolute delight to work with.

BD : I'm thinking William Shakespeare, but he's sort of been at my side forever. He's been a pal.

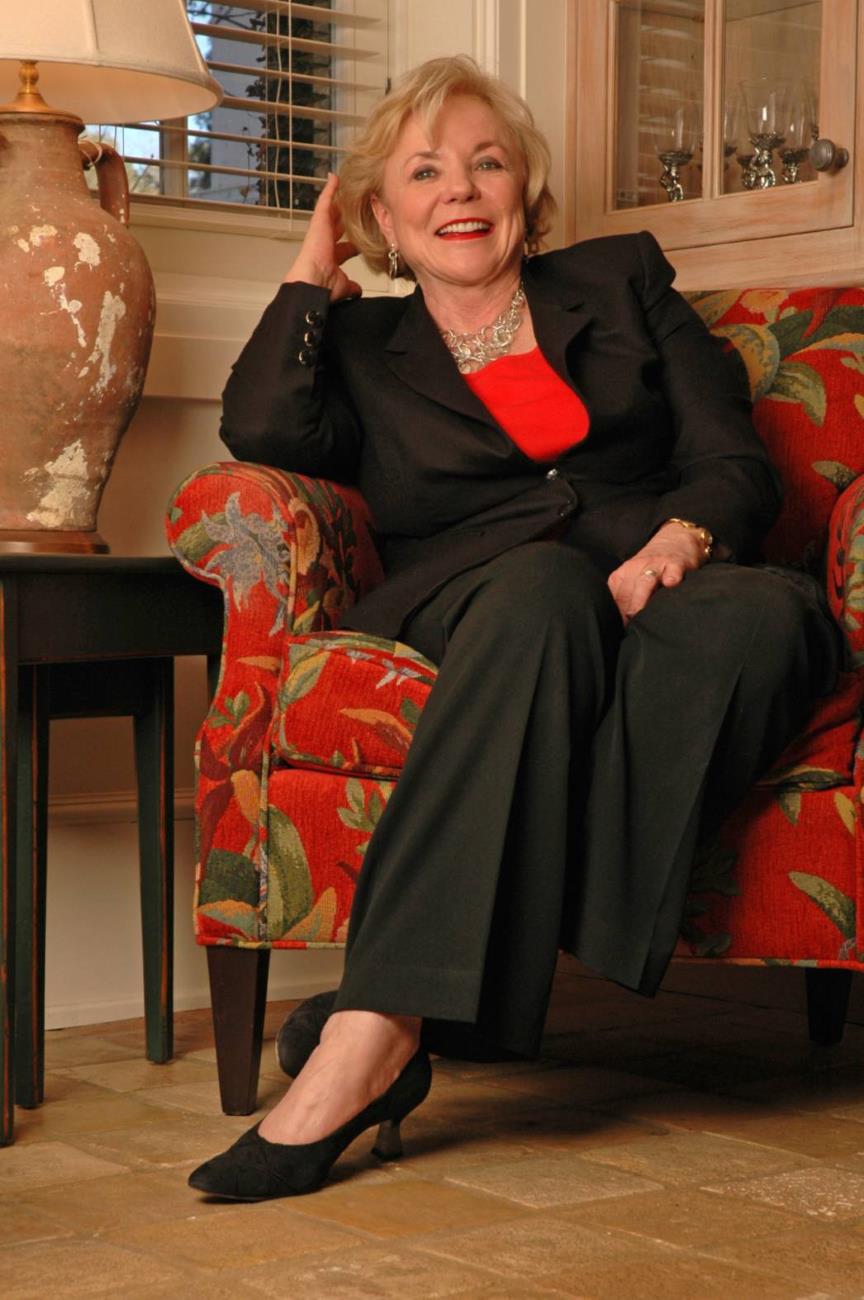

What kind of painting do you do, Bridget ?

BD : If I were to really flatter myself, people have described me as a cross between Chagall and Matisse. It's kind of whimsical expressions; each painting has a small story behind it.

How does the painting process compare to the sense of fulfillment of finishing a script, of having your show on the air ?

BD : In one way, it's more fulfilling in that it's all yours. These are my paintings, and nobody has had any input. No one is saying, "Maybe you should take a little red out, or maybe you should add a little blue." It's just me. My soul is exposed. In another way, it's a much smaller audience. I might have a sell out show, as I did, but it's 25 paintings. It's an intimate audience. I find it equally rewarding.

What kind of impact did your upbringing have on you and the kind of people you are today ?

BD : It had a tremendous impact, and in some ways I'm still fighting it. I was raised by a very strong mother, and she loved me very much - perhaps too much - and to gain independence as a person was very difficult. In small ways, I still fight for that. She raised me not to feel that women are inferior, and I was not to be taken aback by any man. That was a very nice thing to have, not to be intimated academically or professionally. I have been intimidated socially, because she, as a working person, didn't do much socializing, and I was raised first on a farm in Wisconsin where I was rather isolated, and then in a neighborhood in Bel Air where there were not many children to play with, so I have fought to be accepted socially.

JD : I came from a background that wore blinders - farm land, farm mentality. I couldn't go to the Louvre because there were too many naked statues - that was my background. So finding that those blinders didn't need to exist suddenly took my breath away at some point, and I haven't stopped looking around corners, peering under rocks, staring into space, looking into Bridgie's eyes, discovering new things all the time.