By

Christopher Schemering, Soap Opera Digest, 1988

|

|

Home | Cette page en Franšais |

| Santa Barbara

: on the right track |

|||||

|

By

Christopher Schemering, Soap Opera Digest, 1988 |

|

||||

After

experiencing several false starts, Santa

Barbara has evolved into a comedy of errors as it approaches the

four-year mark. If Oscar Wilde were writing soap operas today, the result might

be something like Santa Barbara. With its colorful characters, farcical

situations, and witty, epigrammatic dialogue, Santa Barbara is a comedy

of bad manners one moment, tragic melodrama the next.

After

experiencing several false starts, Santa

Barbara has evolved into a comedy of errors as it approaches the

four-year mark. If Oscar Wilde were writing soap operas today, the result might

be something like Santa Barbara. With its colorful characters, farcical

situations, and witty, epigrammatic dialogue, Santa Barbara is a comedy

of bad manners one moment, tragic melodrama the next.

Along the way, Gina has made love with Mason in a racing ambulance, cooked hot dogs on a hibachi at C.C. and Sophia's outdoor wedding, and baking "Mrs. Capwell Cookies" deadpanned to Santana, who was supposedly allergic to flour, "Doesn't that get in the way of making tortillas ?"

This comedy of errors premiered July 30, 1984 and traced the lives and loves of four families : the powerful Capwells, the blue-blood Lockridges, the middle-class Perkinses, and the Andrades, a low-income Hispanic family. By the end of the first year, it was good-bye to the Perkins and Andrades (as well as a gaggle of insipid blonde beauties.) Soon, nearly every pivotal character had been recast.

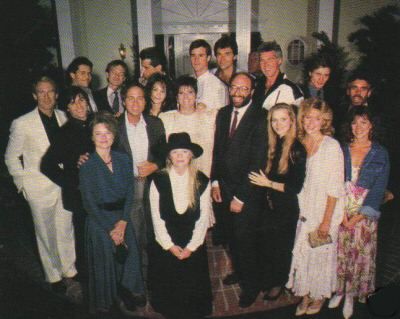

After many false starts, the show made its smartest move, employing actors who had made strong impressions on other shows : Jed Allan as C.C., Judith McConnell as Sophia, Robin Mattson as Gina, Justin Deas as Keith, Kristen Meadows as Victoria, Marj Dusay as Pamela, and Vincent Irizarry as Scott Clark. The joke in the industry soon became : soap stars never die, they merely move to Santa Barbara.

This terrific move has been undercut by the show's revolving door of new characters, who have been cavalierly written out before they - or the audience - could find their bearings. In the last year, we have bid adieu to Brian Bradford, Courtney Capwell, Hayley Benson Capwell, Grant Capwell, Lily Light, Paul Whitney, Jane Wilson, Caroline Wilson Lockridge, Alice Jackson, Gus Jackson, and Carmen Castillo. And, why was the entire Lockridge clan - Minx, Lionel, Augusta, Warren, Laken, and Brick - dismissed ? Structurally, it left the show with only one core family - the Capwells - and no contrast. Secondly, it seemed downright self-destructive to get rid of Richard Eden (Brick) after the actor's Emmy nomination, and the same applies to Nicolas Coster (Lionel), who received an Emmy nomination and the Soap Opera Award for Outstanding Supporting Actor.

Thankfully, the Capwells are such a quirky, murky bunch of individuals that even when the show dumps so many melodramatic situations and pointless plots on their back door, they alternately keep us riveted with their resilience or in stitches with their furtive mischief.

The

powerful, sometimes bullying C.C., who has had three wives declared legally

dead, has been finally blessed with an actor who can really cut the mustard.

(And only Jed Allan could bring such sarcastic brio to a line like, "They ought

to call my biography The Man Whose Wives Refused to Die.")

Sophia is the actress of the family, self-dramatizing yet unpredictable. Ted

(Todd McKee) is the Prince valiant and Kelly (Robin Wright) is a sensual

ingenue, whose lovers invariably end up pushing up daisies. Eden (Marcy Walker)

is the romantic lead, and her star-crossed romance with the Hispanic Cruz (A

Martinez) is still probably daytime's most dynamic love story. The non-stop

obstacles to their eventual clinch were often ridiculous (Cruz's espionage brain

implant) and just plain mean (Eden thrown into a tank of sharks was nothing

compared to her losing a baby she didn't even know she was carrying.) But Walker

and Martinez rise above the fray with all-out energy, humor and sexiness.

The

powerful, sometimes bullying C.C., who has had three wives declared legally

dead, has been finally blessed with an actor who can really cut the mustard.

(And only Jed Allan could bring such sarcastic brio to a line like, "They ought

to call my biography The Man Whose Wives Refused to Die.")

Sophia is the actress of the family, self-dramatizing yet unpredictable. Ted

(Todd McKee) is the Prince valiant and Kelly (Robin Wright) is a sensual

ingenue, whose lovers invariably end up pushing up daisies. Eden (Marcy Walker)

is the romantic lead, and her star-crossed romance with the Hispanic Cruz (A

Martinez) is still probably daytime's most dynamic love story. The non-stop

obstacles to their eventual clinch were often ridiculous (Cruz's espionage brain

implant) and just plain mean (Eden thrown into a tank of sharks was nothing

compared to her losing a baby she didn't even know she was carrying.) But Walker

and Martinez rise above the fray with all-out energy, humor and sexiness.

A recurring theme is the outsider looking in "ambivalent" characters who act as catalysts to move story and create tantalizing familial and romantic conflict for all. The first of these characters was Mason (the always superb Lane Davies,) the black sheep of the Capwells, whose envious and cryptic nature provided the city with a one-man Greek chorus, commentating dryly on all the drawing-room intrigue. With Gina mellowing (well, almost,) the baton of naughtiness has been handed to her sleazeball, aide-de-camp, D.A. Keith Timmons. As played by the hilarious Justin Deas, Keith is such a greedy, sweaty little weasel, one can't help laughing at his antics. With daytime's best romance (Cruz and Eden), funniest couple (Gina and Keith), and one of its most potent triangles (Victoria / Mason / Julia), you'd think Santa Barbara would be set for the big time. But the show is inconsistent in the quality of its long-term stories, daily scripts, directing. (The Wednesday episodes are especially weak.) There are too few core characters for an hour show, and far too many people introduced and run out of town.

Other technical credits are good. Unlike other Hollywood productions, the makeup on the men doesn't look like it was applied by Tammy Faye Bakker and the hairstyling doesn't make the women appear like Vanna White clones of one another. And the Miami Vice-like musical scoring is urgent and stylish without being too overpowering.

With the carefully planned and executed Elena Nikolas plot - which included and affected all the core characters - Santa Barbara was at its prime. (And Sherilyn Wolter gave the kind of performance Emmys were invented for; complete with helmet haircut and huge white teeth, coupled with all the cold, calculated passion that would scare the heck out of anyone.) Again, it was an outsider, whose motivations soon became crystal clear, making the drama become more complex and compelling.

The various parts of the story came together at Cruz's trial for her murder and the surprise testimony of Pamela Capwell Conrad, who everybody thought had jumped to her death off Manhattan's 59th Street Bridge. The November 3, 1987 episode, written by Patrick Mulcahey (Emmy-winning dialogue scribe for Guiding Light), was, simply put, the most thoughtful, witty, literate single episode of the year.

From Pamela's poignant entrance into the courtroom assisted by both of her sons, to a sight gag of Gina wearing an ostentatious black veil, to Keith's comment about Pamela's sudden wealth ("I thought she left New York without a pot to puree in."), to Julia finding Mason drunk ("I'm sorry. I can't help it if I'm drowning. It's genetic."), to the tragic finale in which Mason alternately, taunts his father and laments his status as the untouchable, unloved of the family, Santa Barbara's writing, directing, and acting finally came together in a coherent and entertaining fashion. The mask of tragedy and comedy had melded quite nicely into one. Unfortunately one story line or episode does not a serial make. As the slimy Keith Timmons asked himself once, "Why can't the course of trickery and chicanery run more smoothly ?"